More Draft coverage: 2015 Mock Drafts | 2015 Top 100 | 2014 Draft Grades | News

The first round of the 2014 NFL Draft was one of the most unpredictable in recent memory. It started when the Jaguars selected quarterback Blake Bortles third overall. But things really got exciting moments later, when the Bills traded up from No. 9 to No. 4 to take wide receiver Sammy Watkins.

It was a gutsy move by general manager Doug Whaley, who effectively went all in that Watkins would be the player to catapult the Bills from middle of the road to perennial playoff team. Lofty (some might even say unrealistic) expectations, for sure.

But while Watkins was generally considered the best wide receiver in the draft, he wasn't an otherworldly talent in the mold of Calvin Johnson or A.J. Green, which makes the price the Bills paid --in addition to the ninth pick in 2014, also a first- and a fourth-rounder in 2015 -- even more prohibitive.

In today's NFL, roster building can be distilled to a few simple truths: Find a franchise quarterback, add depth around him, and do it all while walking the salary-cap tight rope. Trading up in the first round -- effectively swapping several draft picks in exchange for the one player an owner, GM or coach has fallen in love with -- almost never pans out.

In a heavily cited study titled "The Loser's Curse: Overconfidence vs. Market Efficiency in the NFL Draft," economists Cade Massey and Richard Thaler concluded that teams are always better off trading down. The thinking: trading down means more picks, which increases the probability one of those picks will work out, whether as a starter or a quality backup.

Massey and Thaler also found that many teams ignore this logic because they are overconfident in their abilities to accurately predict how the one college player they've identified as the next great thing will perform in the NFL.

"There are one or two teams out there that philosophically follow this idea," Massey, who serves as a draft consultant with several NFL teams, told Vox.com recently. "But in my experience, teams always say they're on board with it in January. Then when April rolls around, and they've been preparing for the draft for a long time, they fall in love with players, get more and more confident in their analysis, and fall back into the same patterns."

No idea if Whaley and the Bills fell victim to this or if they truly believe that Watkins is a transcendent talent. But history suggests that Watkins' NFL career won't be discernibly different from a wide receiver the team could have drafted ninth overall, their original draft position. Then there are the 2015 first- and fourth-round picks the Bills sent to Cleveland for the right to move up to No. 4, and the trade seems even more one-sided.

Basically, Watkins not only has to outperform the rest of very deep, talented wide receiver draft class, but do it at such a level that makes it worth giving up a high-round selection in next year's draft, too.

Pro-Football-Reference.com makes it easy to compare players, past and present, with a statistic called CarAV. It stands for career approximate value, and is a means for measuring how productive a player has been throughout his career. (You can read the details here.)

According to PFR.com, the CarAV for the fourth-overall pick is 52. For the ninth-overall pick it's 43. For some perspective, Santonio Holmes (2006, 26th overall pick) has a CarAV of 52 while Jordy Nelson (2008, 36th overall pick) has a CarAV of 42.

If you're thinking, "We'd probably take Nelson over Holmes, even when both players were in their prime," that's our point: At the top of their respective games, both players were really good. But you wouldn't point to one and say, "He's worth swapping first-rounders, and, hell, we'll throw in a first and fourth next year, too."

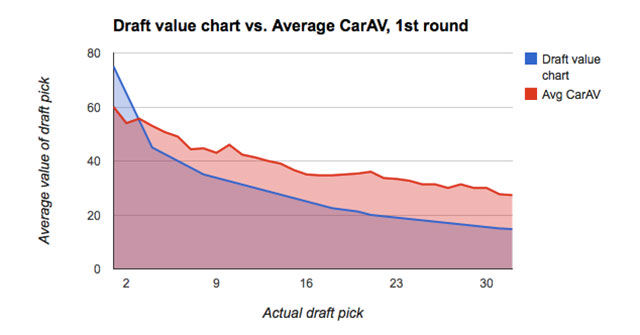

Another issue in the player-evaluation process is the draft value chart. It doesn't carry nearly the cachet it once did, mostly because it's not an accurate representation of how players selected with a certain pick in a certain round will perform. Turns out, the chart overvalues high first-round picks and undervalues mid- to late-first-round picks, which could explain why the Bills gave up so much to move to No. 4

The Bills trade becomes even more troubling when you consider that the picks they parted with have a combined CarAV of 94. (That's 43 for the ninth pick, 38 for the 16th pick in 2015, and 13 for the 115th pick in 2015. Note: We're assuming next year's picks will be in the middle of the round; in the past 15 drafts, the Bills have, on average, selected 16th.)

That, for example, is similar to the production of Larry Fitzgerald (CarAV of 88), Eric Moulds (93) or Roddy White (95).

It's hard to argue that the Browns didn't make out like bandits in this deal; in terms of CarAV, 94 is almost twice as much as 52. Put anther way, the difference -- 94-52 = 42 -- is equivalent to the Bills giving up two No. 9 picks to move up five spots (and this assumes next year's pick is No. 16).

A more reasonable trade based on what we've discussed above (but would never, ever happen in the real world because the perceived price of moving up near the top of the draft is too steep): the No. 9 and No. 115 pick in 2015 for the No. 4 pick. That works out to a CarAV of 43+13 = 56, which isn't far from 52.

But maybe Watkins is that guy to buck convention. It's just that the chances, based on what we know, are exceedingly low. It doesn't help that this was an historically deep draft. Five wide receivers were take-in the first round:

4th pick: Sammy Watkins, Bills

7th pick: Mike Evans, Buccaneers

12th pick: Odell Beckham, Jr., Giants

20th pick: Brandin Cooks, Saints

28th pick: Kelvin Benjamin, Panthers

The CarAV for players drafted with those picks?

4th pick: CarAV = 52

7th pick: CarAV = 38

12th pick: CarAV = 40

20th pick: CarAV = 34

28th pick: CarAV = 32

(Yep, that's right: the CarAV for the 12th pick is higher, on average, than for the seventh pick, which reinforces the imprecision and volatility of the entire draft process. Sometimes players taken later perform better than those selected before them. It happens. A lot.)

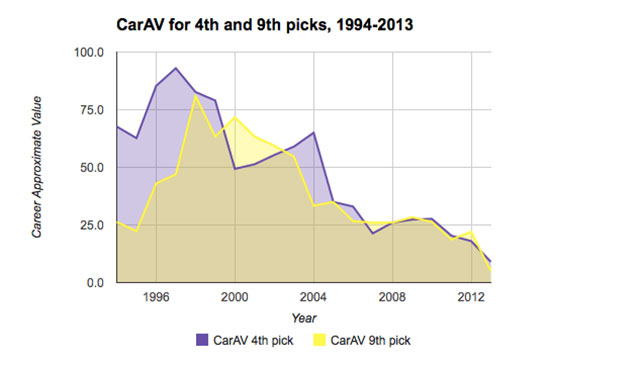

More sobering news: Here's a graph comparing the CarAVs for the No. 4 and No. 9 picks, from 1994-2013:

Other than the first few seasons, there isn't much difference in CarAV for the No. 4 and No. 9 picks. Comparing the averages and standard deviations for these two groups bear this out; statistically speaking, the expected productivity for the fourth and ninth picks are the same. That is, looking at two players, one drafted fourth, and the other drafted ninth, you'd expect them to have statistically similar careers.

The Bills head into OTAs and training camp without much depth, a legitimate concern for a young team without a proven quarterback that just mortgaged its (near) future on a rookie wide receiver.

It's instructive to look at the 2011 Falcons, which gave up their 26th, 69th and 124th picks in 2011, as well as their 2012 first- and fourth-round picks, to move up to No. 6 in 2011 to take wide receiver Julio Jones. The thinking: Atlanta was coming off a 13-3 season but lost in the first round of the playoffs. With franchise quarterback Matt Ryan in place, general manager Thomas Dimitroff figured the team was one player away from Super Bowl contention. (Patriots coach Bill Belichick, friends with Dimitroff, advised against the trade at the time.)

The Falcons won 10 games in 2011, Jones' rookie season, and 13 games in 2012, but were 1-2 in the postseason. In 2013, Jones, along with just about everybody else on the roster not named Matt Ryan, suffered injuries and the team literally limped to a 4-12 record. The lesson: You're never just one player away.

(Two years ago, Kevin Meers of the Harvard Sports Analysis Collective compared the Falcons' trade for Jones to the Redskins-Rams swap that landed Washington Robert Griffin III a year later. In both instances, Meers showed that the Browns and Rams -- teams that were willing to trade down and accumulate draft picks -- were the clear winners.)

The bottom line: When it comes to the draft, the more picks the better. (Incidentally, the Bills have firsthand experience with this; last year, they traded down in the first round to grab Manuel, and used the extra pick, a second-rounder, to take linebacker Kiko Alonso, who had a spectacular rookie season.)

"We look at the draft as, in some respects, a luck-driven process," Ravens assistant general manager Eric DeCosta told TheMMQB.com's Peter King a week before the draft. "The more picks you have, the more chances you have to get a good player. When we look at teams that draft well, it’s not necessarily that they’re drafting better than anybody else. It seems to be that they have more picks. There’s definitely a correlation between the amount of picks and drafting good players."

The takeaway for the Bills: Rarely does trading up pay off. Good players can be found throughout the first round -- and beyond. History might prove us wrong, and it would be a great story for a franchise that hasn't had a winning record since 2004, when Mike Mularkey was coach and Drew Bledsoe was quarterback. But the reality is that good teams seldom trade up. Good teams are also good because A) they have a franchise quarterback, and B) a lot of quality depth around him. Buffalo, as it stands, has neither.