The NCAA says it is not legally responsible for any academic fraud that may have occurred at North Carolina . College sports' governing body wants a lawsuit filed by two former North Carolina athletes moved from state to federal court.

In January, former North Carolina women's basketball player Rashanda McCants and former football player Devon Ramsay sued the university and the NCAA in relation to the school's academic scandal with fake classes. The complaint, filed in North Carolina state court, accuses the NCAA of negligence because it knew of other instances of academic fraud for the past century and refused to implement adequate monitoring systems.

"This case is troubling for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that the law does not and has never required the NCAA to ensure that every student-athlete is actually taking full advantage of the academic and athletic opportunities provided to them," NCAA chief legal officer Donald Remy said in a statement, adding that many athletes maximize their educational opportunities.

In a news release last Friday, the NCAA said moving the case to federal court is appropriate "based on the federal law that confers jurisdiction over class actions of this nature to the federal courts." Former North Carolina football player Michael McAdoo filed a similar suit in federal court last November against only North Carolina, not the NCAA.

Michael Hausfeld, a lead attorney for McCants and Ramsay, said in January that he sued in state court because, "If you look at the legal ability to sue in North Carolina, you can't do it in federal court. There's statutory immunity." The other attorney on the McCants case is retired North Carolina Supreme Court justice Robert Orr.

Hausfeld is the attorney who recently defeated the NCAA (pending appeal) in the Ed O'Bannon case over the commercial use of athletes' names, images and likenesses. His latest suit attempts to attack the heart of college sports: The NCAA's stated mission of educating athletes in exchange for their participation in sports.

The McCants suit attacks the NCAA's knowledge that time demands for players often exceed the weekly 20-hour rule; the NCAA's lowering of initial eligibility standards through the years; and the NCAA's focus on progress toward degree rather than the quality of the education. The plaintiffs seek unspecified damages and the formation of an independent commission to review academic integrity at NCAA schools and compare the education between athletes and the rest of the student body.

The NCAA said the McCants lawsuit "misunderstands" the association's role with member schools and ignores "myriad steps" the NCAA has taken to assist athletes in the classroom. The NCAA cited eligibility standards for players and Academic Progress Rate requirements that can result in teams missing the postseason.

The NCAA said it remains "vigilant" in reviewing violations of academic misconduct and penalizing when appropriate. Last June, the NCAA said it had re-opened its investigation into North Carolina.

One legal strategy used by the NCAA in this case has become apparent.

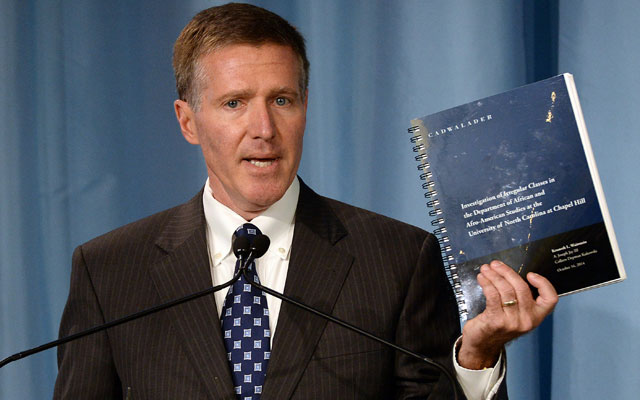

"Courts have concluded in similar cases that standard-setting organizations cannot be held liable for the actions of their members," NCAA outside counsel Walter Dellinger said in a statement. "The NCAA is not legally responsible for any academic fraud that may have occurred at UNC."

Meanwhile, Mary Willingham, who helped expose North Carolina’s academic fraud to the Raleigh News & Observer in 2011, said Monday that she won’t accept the NCAA’s request to be interviewed in the NCAA investigation of North Carolina.

“If they’re not going to be responsible in real court or under United States law for providing real education as a regulatory bylaw, then why should it matter because all I have to tell them is students didn’t get a real education?” Willingham said.

Willingham said she met with NCAA enforcement officials on Feb. 20 but declined to be interviewed upon learning that her statements would immediately be turned over to North Carolina as part of a joint investigation. At the time, Willingham was completing a settlement with North Carolina over a lawsuit she filed last summer contending that the university retaliated against her for blowing the whistle about academic fraud.

“I settled, but on the day of the settlement both parties agreed not to sue each other up to a date that has now passed,” Willingham said. “Now I’m going to meet with the NCAA and open myself up to litigation where the university could sue me over something I did or didn’t say? What if I say to the NCAA I knew this, but North Carolina says in 2007 you didn’t say this so you were lying and now we’re going to sue you?”

Willingham was harshly criticized by North Carolina last year when she alleged some of the athletes placed in the fraudulent classes had reading skills at elementary-school levels. North Carolina hired experts to refute her research, but didn’t dive into diagnostic tests and other materials that might show the athletes’ preparedness academically, according to The News & Observer.

NCAA assistant director of enforcement Todd Shumaker sent an email Monday to Willingham’s attorney asking if she is now willing to be interviewed given her settlement. Willingham said she would have spoken with the NCAA for several years and was under the impression that everything she provided North Carolina had been turned over to the NCAA.

“I figured if they wanted to talk to me, they would call me,” she said. “As time went by, I was pretty surprised I hadn’t heard from anybody. I figured just like the university, they didn’t want to discuss this. … If the NCAA wants to depose me and take me to court, do it. Otherwise, game over.”