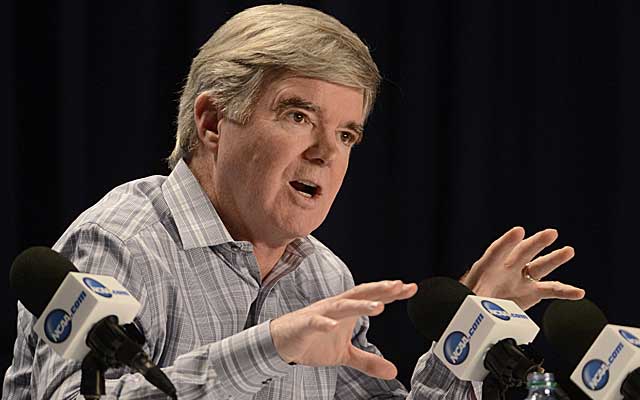

NEW YORK -- There are no shortage of issues facing NCAA president Mark Emmert, who calls the next 36 to 48 months "a seminal moment for college sports."

A judge's injunction in the Ed O'Bannon case could allow college athletes to receive deferred compensation as soon as August 2015. Another lawsuit that seeks a free market for college athletes is getting started.

At any point, the National Labor Relations Board could rule on an appeal about a regional director's opinion that Northwestern football players are employees who can unionize. The NCAA's attempt to get a concussion settlement approved by a judge has hit a few bumps.

Congress continues to show interest in college sports through hearings and now some members want a presidential commission to examine NCAA issues. Through all of this, Emmert's effectiveness has been questioned, most pointedly when Sen. Claire McCaskill wondered aloud last summer at a Senate hearing why Emmert's position even exists.

"I do believe the next 36 to 48 months are going to be really, really important in the history of college sports and whether college sports survives as we know it today," Emmert said. "It's going to be very dynamic, that's for sure."

In a wide-ranging interview Tuesday with CBSSports.com, Emmert discussed among other topics the need for NCAA members to soon consider the implications of the O'Bannon ruling; his belief that an NCAA court case will reach the Supreme Court; his concerns about a presidential commission in Congress; his willingness to allow college basketball players to return after turning pro; and some of his own failures four years into the job as NCAA president.

Q: Do you see the future of college sports being shaped by courts, by NCAA autonomy, by Congress, or by all of the above?

Emmert: I think there's going to clearly be a role for the autonomous five (conferences), but I think there's been some overstating of that. Those five conferences have autonomous support over a small part of the rulebook and the rest of it they're going to do in conjunction with all 32 D1 conferences. … Clearly the outcome of some of the legal cases has potentially a significant impact. We feel really, really good about our legal positions. While you're never looking forward to trials, they give you an opportunity to state your case.

Q: Do you have interest in the NCAA seeking an anti-trust exemption?

Emmert: We don't believe we need one right now because college sports is not violating antitrust laws. … The O'Bannon case and the Jeff Kessler case go right at antitrust laws and say universities and conferences and the association violate antitrust laws, and we disagree so we'll just have to wait and see where that goes -- probably the Supreme Court for another ruling in college sports that we haven't had in 30 years.

Q: So you anticipate a case going to the Supreme Court and the NCAA is prepared for that?

Emmert: Absolutely. Some of the legal arguments being brought out by plaintiffs, there's just not a middle ground. It's not something you can settle out. It's not like a traditional case. It's a question of are these professional employees who can earn whatever they earn in an open market, or are they college athletes who play inside an association?

Q: If the NLRB ruling comes out unfavorably against Northwestern, is there any recourse for the NCAA and Northwestern, or is it your view that it sets the precedent for private universities that athletes are employees and can attempt to unionize?

Emmert: Northwestern could go to the courts and could have recourse through the courts, and every indication is they would do that if the NLRB rules supporting the local NLRB administrator. I'm sure the members would want us to be supportive of Northwestern in that case, and that's certainly every indication we've given. And I'm sure it winds up in the courts. I can't imagine it not.

Q: What role, if any, could Congress play in college sports?

Emmert: I don't know. Congress has expressed a deep interest in college sports. Both the House and the Senate have held hearings. Members of Congress have espoused strong views. I've been meeting with them routinely for several months. It's not clear precisely what, if anything, you would want Congress to do but everyone is in agreement college sports is a very integral part of society and they don't want to see college sports go away. You hear concerns about student welfare, you hear concerns about small schools still being able to play games, you hear concerns about the whole unionization issue. So Congress has a keen interest in this subject. But whether or not that ever converts to legislative action, we don't know.

Q: There has been a bill introduced that would create a presidential commission in Congress for college sports to examine a number of issues. Do you think that's a good idea?

Emmert: That's up to Congress and the president to decide. I think one has to be extremely careful not to turn this into -- pardon the pun -- a political football. We've been down the road of engagement at the highest levels of government before 100-some years ago. It led to the formation of the NCAA. So this isn't unprecedented. On the other hand, these are very challenging times, so if there's going to be a commission or any other engagement, I hope it's focused and meaningful and that it's not done for political reasons, but because people are generally interested in the issue of college sports.

Q: Increasingly, more people are asking why not let athletes make money off their name? Why not be able to make money off autographs or endorsements and possibly have it regulated in some way by universities? Could you ever support that?

Emmert: I think it's clearly an active debate and discussion. What the member schools are most concerned about is how do you maintain a competitive balance in a system where schools are in position where they can outbid one another for a paid autograph or car endorsement or pick your model? And doesn't that simply become pay-for-play under a different name? That's where the debate always breaks down. It's an integral part of the O'Bannon case. We're appealing that, so we'll see where it winds up.

Q: You said after the Todd Gurley suspension for being paid for autographs that it's a good time to have the debate over that NCAA rule. Has that happened? Are there ideas?

Emmert: I think we're going to have a conversation about it in January when the board comes together and the council comes together for the first time (in the new NCAA governance structure). I think it is time to say, do we want to have this rule or not? … Do you want to have those rules enforced? Because you can't put those rules in place and enforce it and say we don't like the rule. That's the point I was making.

Q: The NCAA is appealing the O'Bannon ruling. But there is a federal judge's injunction out there saying she believes schools should be allowed to pay football and men's basketball players deferred compensation for use of their names, images and likenesses. The reality is that at some point soon this could be happening to college sports. What is the NCAA doing to prepare for that possible new world?

Emmert: Her injunction would go into effect in August 2015, so it's fast approaching. That's probably going to be the single biggest topic of conversation among university leaders and athletic directors in the coming months as we get this new governance model in place. Because right now, it's not clear what the implications of that would be and what rules could or couldn't be in place. It's a very ambiguous place right now.

Q: The judge's injunction would allow the NCAA to cap the deferred payment at no less than $5,000 per year. It's not clear to me who within the NCAA creates that rule. Is it the entire NCAA, or is it the major five conferences through autonomy?

Emmert: Right now our rules don't allow what she describes, so to put in place a new rule that is consistent with her opinion would, I assume, take all of the Division I membership to vote, not just a subsection.

Q: Assuming the O'Bannon injunction happens, what do you think that new world looks like in August 2015?

Emmert: I don't know. I think if we don't have agreement on a rule then you could ostensibly have -- and I think this is the argument in one of the other lawsuits -- a school paying anybody whatever they want. I don't know anybody inside college sports who works in higher education who thinks that's a good idea. The reality is we don't know what that looks like.

Q: There are a couple cost of attendance proposals out for consideration to provide an extra stipend to athletes. How do you think cost of attendance plays out in terms of which athletes get the extra money?

Emmert: Some schools may say we're only going to do full cost of attendance in these certain areas because we can't afford to do them everywhere, so we'll emphasize these sports. Or some schools will be able to do it across all of them and they may well do that. Those are going to be local decisions each campus has to make, just like they decide on how much to spend on new facilities.

Q: What did you think of how Michigan handled Shane Morris' concussion this season in which he returned with concussion-like symptoms?

Emmert: I haven't seen a full review of everything that happened there. I'm very pleased on a number of things that happened around concussions. The NCAA and the (Department of Defense) launched a $30 million concussion study that's already the biggest concussion study in history. … I was really pleased we came out with the practice guidelines and all the schools are taking it very seriously. I'm really pleased by things like the Big Ten this week saying we're putting in place these mandatory policies that are aimed at preventing anything like a Michigan or another situation to occur.

Q: That raises the obvious question of when, or if, the NCAA will impose penalties if schools violate concussion protocol standards?

Emmert: Well, the NCAA is the members. We are nothing more than those individual schools and those conferences. I very much would have been advocating there be association-wide policies that go beyond where are now. We have policies in place. People follow those policies to the best of anybody's knowledge. I'd very much like to see something like the Big Ten did spread across all of the NCAA. I'd be very supportive of it.

Q: How would it be enforced? Would someone investigate if there are violations of concussion protocol?

Emmert: Well, that's what you have to figure out. What does that model look like and who does it? In my opinion, it doesn't have to be the national office. We don't have the medical team to go out and conduct those investigations. It could be at the conference level, it could be at the institutional level. There are a bunch of different ways to manage this, but I do think it needs to be done.

Q: What was your reaction to the Wainstein report at North Carolina that showed how deep-rooted the academic fraud was there among athletes and the university?

Emmert: I was impressed the university committed the energy and resources to do that study and they made it public and they rolled it all out there, and that's a very hard thing for a university to do. Here's one of the great universities on Earth and they're working very, very hard to get this right. Everybody looking at that was I'm sure disappointed. But by everything I've seen, they're incredibly serious about it and working very hard at it. And at the end of the day, only the universities themselves can take responsibility for that. You can't have anybody from a conference office or national office go in and say here's how you teach English 101. No, only the schools can do that.

Q: What delayed the NCAA's investigation of North Carolina?

Emmert: They weren't really delays. The staff went in originally looking at an issue unrelated to any potential academic misconduct and was focused entirely on that and finished that up, and then as all of this issue unfolded, then the investigative staff reengaged with the university. The university has been very forthcoming working with our people.

Q: What's the status of the investigation?

Emmert: It's still an ongoing investigation. UNC has been very open and forthcoming and it's been a good project, as far as i can tell. I stay away from investigations. There's a firewall between me and investigations. I don't have anything to do with them, despite what people occasionally think. That's not my job.

Q: Did that change for you after the controversies with the Miami and Penn State cases?

Emmert: That's always been like that. Penn State was unique in every way, in its scope, its impact. It was unique in the magnitude of the misconduct and called for, and got, a unique situation.

Q: Looking back at Penn State, do you have any regrets that you handled the discipline in the Jerry Sandusky child sex-abuse scandal outside of the normal enforcement process?

Emmert: I think the (NCAA) executive committee and the board handled it very, very well. I'm sure there could have been things handled better from a communication view to the public. But in terms of the solution that was crafted and the sanctions that were put in place, the executive committee, the board and I think they wound up in exactly the right place. … It had the intended impact for the university to demonstrate its seriousness. Do people like it? Of course not. There's nothing to like about a situation like that. I think it's easy to sit here today a little more than two years later and forget the trauma that was going on right then. I think it's served its purpose.

Q: The implication through emails in a court case involving Penn State is you used leverage to bluff the university into accepting the consent decree. Was that the case?

Emmert: We have a trial coming up (in January) on all those issues so I'm not going to talk about it. The advantage of a trial is you get to put the entire record out, not a sound bite.

Q: Some conference commissioners have said they're open to the idea of outsourcing NCAA enforcement. I'm not sure what that even entails. What is your reaction to that concept?

Emmert: If there's a more effective and successful way of doing that, it would only be sensible to look at that. I'm in favor of looking at whatever models work better. But I'm like you: I don't know what outsourcing means. You can't have subpoena power. Only governmental entities have subpoena power. I mean, you could outsource to the FBI, I suppose. I don't think people want that. It doesn't change the power or authority so I don't know what it gets you outsourcing. But having said that, I'm more than happy to hear any of those arguments.

Q: NBA commissioner Adam Silver continues to push to increase the NBA age limit from 19 to 20 years old. Do you continue to speak with him on this matter, and what's your sense on whether the NBA Players Association would support this?

Emmert: I have talked to him a bit about it. I've also heard from the new executive director of the Players Association and her comments. They both have important points to make, and the last thing the NCAA wants to do is get in the middle of their labor relations. That's not our business. I think that there's a deep interest among my universities that they want to make sure we're doing the best by young men and women who play games, and not have a young man, a boy, feel the necessity to go to college to touch a base to jump to a professional sports league and not take their education seriously. That's a fundamental problem.

Q: Theoretically, couldn't the colleges stop signing one-and-done players, even though it's unlikely given competitive reasons?

Emmert: First of all, it's hard to tell who's a one-and-done. That's an individual choice, as it should be. I get that. But there's a lot of issues here that need to be addressed. I think members need to look at the relationship between college sports and professional sports, and I don't know what this looks like, but allow young men that are playing college basketball, for example, to get a much better sense of the marketplace. Right now, the only way they can really get a clear picture of the marketplace is declare for the draft and step away. Most of our rules say now you're done. Go over there, you're finished. Is there a way for those who aren't going to play in NBA to learn from somebody in the outside world who says, look, you're not going to play professional ball?

Q: So give players representation. We already know that happens in baseball, although NCAA rules still restrict those players to an extent.

Emmert: I think that's what I'm talking about. … I'm more than happy to have us all consider what should the model look like in relationship between us and professional sports leagues. OK, if you go play a year in the D-League, does that mean you never, ever come back to college to play? I don't know. Maybe that's something we need to think about.

Q: So if a player gets drafted and goes to the D-League, you'd be OK with the player returning to play in college?

Emmert: I'm open to consider that. But again, that's me and not the members. I'm sure coaches would have their concerns about that and I understand why. You wouldn't want it to be a revolving door that one year I'm here, the next year I'm in the D-League. You'd have to structure it.

Q: Sen. Claire McCaskill had a very pointed comment directed at you at the Senate hearing last summer of why your role even exists. I wonder about that question in light of we know the courts will decide a lot of things and NCAA autonomy will decide a lot of things. What do you view the NCAA president's biggest role being right now?

Emmert: Let's back up and look at what the association does or doesn't do. You occasionally get people saying the NCAA is irrelevant and shouldn't even exist. Do you want to have national championships? Do you want to have consistent rules across higher education? Do you want to have interleague play around all of the sports? Do you want to have an enforcement model that conducts enforcement? Do you want to have a shared governance model? if you want those things, you have to have some entity that does it. … The role of the president is not to be the guy who makes decisions, but a guy who helps keep people focused on those decisions, help them move past the issue du jour to bigger, broader issues. He's the mediator, shuttles diplomacy, does all of the things to get the membership to focus on issues that serve college sports and athletes over the long run. That's how I see my job in all of this.

Q: How much longer do you want to remain president?

Emmert: It's been a challenging four years, to say the least. But I think there hasn't been enough recognition, not of what I've done, but what the members have done over that four-year period. We had ridiculous rules around food because of concerns about competitive fairness. Now we say just feed kids, stop worrying about it. We had a rule that says not only shouldn't you give multiyear scholarships, you can't give multiyear scholarships. We now have conferences saying if you don't give multiyear scholarships, you can't be a member of this conference. We had a board pass a miscellaneous expense allowance to move to full cost of attendance that was blown out of the water by the membership, and in January we're going to have a bunch of conferences say you must do this.

Q: Hasn't a lot of that been forced upon the schools due to legal cases and rulings?

Emmert: If you go back to the summer of 2011, about 65 university presidents came together and outlined an agenda of all the things they wanted to get done in as rapid fashion as we could. At the time, we weren't under any of the pressing threats we're under now. … If you look at the four years since then, there's been huge progress. Are all of the outside factors part of that? Well, of course they are. But nonetheless, we're winding up in that place. The point is as long as I can help moving them in that direction, I'm having fun and want to keep doing it.

Q: How many more years are left on your contract?

Emmert: I'm on until 2017.

Q: Could you foresee a situation where you don't finish that contract?

Emmert: No. It's an important time in college sports.

Q: What are your biggest regrets in your tenure?

Emmert: Oh gosh, plenty. If you go back to the first nine months, got in, had this presidential summit, identified a to-do list. I ran at that too fast. I underestimated how hard it is to build consensus in the membership. In the process I didn't bring together all the constituent groups that needed to be together. Clearly, athletic directors weren't sufficiently a part, faculty reps weren't a part. I would have loved to have moved an agenda that brought more people in, even though it was a controversial agenda. I don't know if we could have gotten there any faster, but we could have gotten there with less pain. I've been impatient in a number of ways around things. It's taken me a while to learn how to be an association leader. It's a different job than anything I've ever done or most people have ever done. It took me a while to figure that out.

Q: There was a very real perception out there that you wanted a lot of attention. Was that the case?

Emmert: I was hired by the presidents of the executive committee and one of the things they said was, look we need to have the president of the NCAA be well known and have you, Mark, be the face of the NCAA and talk about all of the things we need to get done. So I went out and did that. And as a result, that created some of those perceptions. In retrospect, I think it would have been a lot easier to get where we are today if instead we would have been shoving university presidents and ADs out more in front of the camera to get people to understand. Too many people believe the association is like the NFL and some ruling entity sits in Indianapolis and decides everything. The association is all of the member schools. It's complicated, not very convenient, but that's what it is. I could have handled that a lot better.