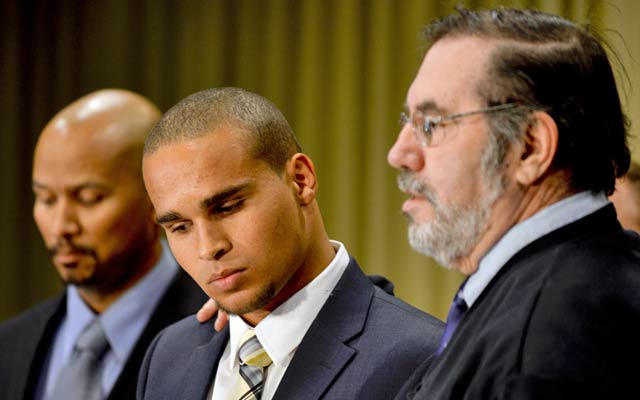

Kain Colter leaves no wiggle room – playing college football is a job.

Colter, the former Northwestern quarterback and face of the first legitimate efforts to unionize college football, said as much at this week’s National Labor Relations Board hearing in Chicago. Northwestern players often worked 50-60 hours a week on football-related activities, Colter said.

How much was Colter paid for those hours? Well, he wasn’t, but if we’re talking value, he got a yearly scholarship of, say, $60,000.

He probably received ancillary benefits such as strength and conditioning programs, meals, medical care (assuming the school is taking care of it – a point of emphasis for the newly formed College Athletes Players Association), apparel, available funds for family emergencies if necessary. Schools front the bill in exchange for the athlete to go to class and produce on the field.

Now imagine Colter getting a W-2 in the mail for that $60,000 amount and a few of those benefits, too.

Some college football officials – and even a tax attorney out of Chicago – certainly can. When Colter and the CAPA filed a late January petition to unionize on behalf of Northwestern players, a few athletic directors privately wondered whether unionized players would be taxed like normal work-for-pay employees – without the pay part, only the scholarship value.

Now, schools would have their reasons to shun unionization. They don’t want to pay unemployment insurance, workers compensation, disability insurance and pension plans, all elements that might be negotiated in collective bargaining. Maybe that's in play with driving tax agenda.

But as one high-ranking official says, the taxation issue ‘isn’t a scare tactic’ from schools to dissuade the players.

It's reality.

“If they are categorized as employees, I’m not sure the IRS cares much about the other circumstances,” said the official, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “Everyone involved needs to understand what the various consequences are for both parties.”

This all sounds a little crazy, right? And to think the Northwestern players aren’t asking to be paid by the schools, at least not yet. They want to help drive legislation in college athletics and reform injury/concussion care. Players haven’t even received a stipend yet, and now they’d have to pay thousands they don’t have on taxes?

Kansas State AD John Currie said Thursday any talks about player taxation would be purely conceptual at this point. But he acknowledges the dynamic.

“It’s one of the potential unintended consequences of a well-meaning action,” Currie said. “We all desire to continue to make progress in enhanced medical care and student-athlete welfare.”

Since an IRS spokesman declined comment on the tax implications of college athletes unionizing, CBSSports.com reached out to a tax attorney, Ed Hannon of Freeborn and Peters LLP, for clarity.

Hannon cited Sec. 117 of the “Current Internal Revenue Code,” which essentially states that though a “qualified scholarship” is not considered gross income, that can change if the scholarship money “represents payment for teaching, research or other services by the student required as a condition for receiving the qualified scholarship or qualified tuition reduction.”

In other words, if an employee is doing a job unrelated to his major as a condition of getting the scholarship, “those dollars will likely be fully taxable,” Hannon said.

Hannon advised there are exceptions, such as when an employee does a job relevant to what he’s studying.

You want to redefine pay-for-play? Try an offensive lineman/biology major getting taxed on $60,000 because his football work doesn’t align with his major.

That’s why Hannon wonders whether schools will create college football majors as a loophole for players – that’s if they want to help. Or maybe, as Bylaw Blog author John Infante from athleticscholarships.net points out, a physical education or coaching major would suffice as a bargaining chip for tax-free status.

“The threshold question in addressing this is how do they get around that problem?” Hannon said. “You get the scholarship but you have to play football for us, and we’re going to pay you X dollars to play football, that can cause all of tuition to become potentially taxable. If they are employees, they’d have to go by fringe benefit tax rules that can haunt every employer.”

Currie, however, doesn’t see a college football major getting approved by higher-ups any time soon.

As for additional benefits, an athlete using a school’s football facility is a “no brainer” tax-free benefit, Hannon said. But using a strength coach? Could be a taxable benefit depending on whether that coach is deemed necessary for the student's major, Hannon says. One BCS-level AD said his department’s assessment values its yearly football strength and conditioning program at about $9,300.

Since IRS bylaws don’t address college athletes unionizing, perhaps the system will change to accommodate that dynamic, which Peters said could be a “tax disaster" but not impossible.

As for the players, the man in charge of CAPA says he doesn't foresee this as a problem.

Ramogi Huma, who started CAPA and is a long-time advocate for player rights, says players might get taxed on room and board – and in some cases already do. But Huma seems fairly certain players wouldn’t front the bill on the whole thing because players aren't trying to rework the scholarship model. CAPA can argue players don’t get a scholarship for academics -- they get it for athletics.

“I don’t think anyone envisions players negotiating the scholarship away,” Huma said. “If anything it would be protections to a scholarship. Anything on top would be a net gain.”

But since the IRS language leaves room for interpretation, as Hannon points out, rules might need tweaking to accommodate this unique relationship.

At the core of the unionization issue, Infante said, is whether Northwestern players will get guarantees on issues such as health care and multi-year scholarships. But clearly they wouldn’t want a tax hit as a result, and since colleges look to avoid the additional costs that new employees would bring, perhaps the players and the NCAA can agree to a settlement, Infante said.

By waving the tax issue, are schools taking one step forward and two steps back in what they promise?

“Right now one of the big pushes is that the scholarship isn’t big enough, it doesn’t cover the full cost of attendance, so you add the stipend,” Infante said. “Then you say you’ll open up more scholarship taxation?”