More college football: Jon Solomon | Dennis Dodd | Jeremy Fowler | Latest news

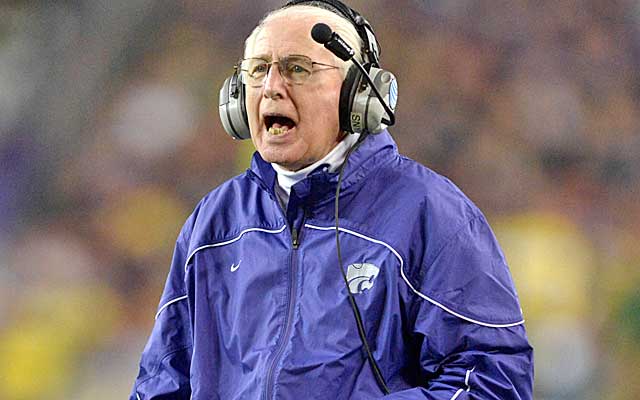

If you really want to get to Bill Snyder, slow him down.

Pull him over. Chat him up. Stop him in the hall on the way to a meeting. A few media members have tried this casual approach following the in-season Tuesday pressers and been rebuffed.

This is the coach who famously considers sustenance a nuisance. This is a man who moved into his Kansas State office -- decades ago now -- before there were four walls to surround it. Bill Snyder doesn't do chat, casual, architecture or food if they fall outside the strict parameters of his schedule.

He sure as heck doesn't do a walking boot on his left foot at age 74.

"I've never been in a cast in my life," Snyder said recently during the Big 12 spring meetings in Phoenix. "It's been the most frustrating thing I've ever encountered on a personal nature in my life."

That's quite a statement considering his professional and personal life. Or maybe it's just a momentary nod to hyperbole. Whatever, you do have a glimpse of the man's frustration.

A tendon that runs from the foot to the ankle has been pulled off the bone. Snyder didn't know until a team doctor happened by the training room where the coach was receiving treatment for another ailment.

Doc: Have you noticed this bump down here?

Snyder: Not that I know of.

Doc: That's your tendon, that's supposed to be attached down here.

What has followed is a cast. Rehab will be next -- weeks of the man being off schedule, slowed down. Hey, who needs a functioning tendon when there's film to break down?

"Normally I can get up and be in the office in 15 minutes," Snyder complained. "It takes me 15 minutes just to get from the bed to the sink now."

The pace of that morning routine still puts him ahead of a sizable portion of his age demographic. That's also a glimpse at some soon-to-be history. FBS' oldest active coach will turn 75 in October. At that moment, Snyder will become immediately eligible for the College Football Hall of Fame. No waiting. The career winning percentage requirement of .600 will be more than assured (.664).

There shouldn't be any argument either. Unless voters suffer collective memory loss, Snyder will be a member of the 2015 class, the fourth active Hall of Fame coach ever.

Told all this, Snyder becomes quiet, uttering something about it being "genuinely humbling." It's clear he doesn't want to think about such milestones.

That's probably because Hall of Fame suggests some sort of end, a slowing down. The three other names on that (formerly) active list would give anyone pause: Joe Paterno, Bobby Bowden and all-time winningest coach John Gagliardi.

The process -- probably unbeknownst to Snyder -- has been through a sort of a Hall of Fame wash cycle at Kansas State. The school was ready to nominate him for the 2014 class to be announced Thursday. It got an interpretation that Snyder would have to wait until he actually turned 75 (Oct. 7) to be eligible.

The 2014 season, then, will be defined as something between a farewell tour and lifetime achievement. In his 70s alone, the man has come back to coach -- some say save -- K-State a second time. He has produced a Heisman finalist (Collin Klein) and a Big 12 champion this decade. That 2012 team was on track to play for the national championship until a mid-November loss at Baylor.

Since returning in 2009 he has won almost two-thirds of his games, 42 total. Two-hundred career victories is within sight at a school than had only 299 in its history when Snyder took over in 1989.

No wonder they erected a statue of him prior to last season.

During the process the sculptor requested an interview to get a better idea of his subject. He encountered "... this wall that was not going to be penetrated, you know what I mean?" Mysterious, inscrutable, secretive. All those labels fit. A quarter century after he came to Manhattan, we know little of the "why" of Bill Snyder.

Even less of the "how." The us-against-the-world mentality may have been invented in The Little Apple. As constructed, the Wildcats seem like they could contend for the Big 12 title any given season. Snyder still is the master shaper of underestimated talent, perhaps the best junior college recruiter in history.

He has molded All-Americans out of junior college recruits, going against the age-old saw, "There's a reason why they're in junior college."

"That's a story I hear all the time," Snyder said. "There's a reason we're all on earth. Sometimes nobody gave them an opportunity to go anywhere else."

If he has an exit plan, it is not evident. A question about Snyder having input in picking his successor is met with a clipped reply: "I would hope that I would."

There are rumblings that Snyder would like his son, Sean -- the special teams coach -- to take over, but that's a discussion for another day. When the ultimate transition comes it will be on some level wholly uncomfortable. Kansas State has been through it once.

Snyder's first replacement -- Ron Prince (2006-2008) -- showed how monumental the task can be. The unprepared Prince went 17-20 in three seasons, going to one bowl game. Prince wasn't incompetent, just inexperienced, certainly not the right personality to be a head coach following a legend.

Maybe the only way the Wildcats are here right now is because Snyder decided to come back. But how do you become a miracle maker a second time? Whether Snyder retires next year or goes past 80, Kansas State is a program that has to get a toe hold on the sheer face of competitiveness each day.

The Lazarus-like story of Kansas State football has been told so many times it should be a bible chapter. It earned him at least input upon his first retirement. The renaming of KSU Stadium had to be adjusted to the coach's wishes.

Bill Snyder Stadium had to become Bill Snyder Family Stadium because "Nobody suffers more than a coach's immediate family. I've got five children, eight grandchildren. I think I'm a good family man. I don't play golf, I don't go to the bars. If it isn't football, it is family."

Except that like a lot of his peers, Snyder can act the contrarian. If it's all about family, why did he come back a second time diving into his job with that familiar intensity?

Sometimes that drive was as infamous as it was brilliantly fierce. In 1998, that intensity overflowed. Ten years into the Miracle in Manhattan, the Wildcats blew a 15-point fourth quarter lead to Texas A&M, losing the 1998 Big 12 championship game in overtime.

A berth in the first BCS title game, blown. Back then Snyder called it "indefinable disappointment." He referenced the deaths of his mother, grandfather and the paralysis of his daughter Meredith in an auto accident.

"I'm almost embarrassed to say it," Snyder said following the game, "but I had the same kind of feelings."

That was quite a statement, considering his professional and personal life. Or maybe it was just a momentary nod to hyperbole. Still, a football game compared to a death in the family? Who was this guy whose fire burned so hot, but was so mysterious, so inscrutable, no secretive?

Sixteen years later there is no clear answer.

If there is any slowdown these days, Snyder seems to recognize his role as a sage, an oracle. He jokes about his now-famous hand-written notes the coach sends to both opponents and K-State Rhodes Scholars. Keyboards be damned.

"When people do something that is special for the right seasons, it's just acknowledgement," he said.

The game cares what he says. It should. There is reform in the air for the game, for athletes, for what it means to play college football. Snyder is concerned it will go too far, upsetting the current college foundation that gave rise to that Manhattan Miracle.

"If you disband all rules, whoever makes those decisions are people that probably don't have children," Snyder said. "I can't imagine a home with children without rules and regulations."

With that a father, a coach and a sage limped off down a hotel hallway -- that darn left foot slowing him down.