CLEVELAND -- About a quarter past 8 o'clock Pacific Time on Sunday night, LeBron James spiked the ball, sent it hurtling toward the pinwheel roof of Oracle Arena and let out a visceral roar.

The planet's best basketball player and what was left of his Cleveland Cavaliers had taken an improbable leap toward turning the NBA Finals against the Golden State Warriors upside down.

In the locker room, he struggled to squeeze his throbbing, aching legs into a pair of Nike compression tights, then walked like your average desk-bound, middle-aged reporter toward the interview room.

"Did you see how I walked in here?" he would say at the podium. "I'm feeling it. I'm feeling it right now for sure."

Forty-six hours and three time zones later, 12 seconds into Game 3, James got the ball in isolation from the left side against Harrison Barnes. He pivoted on his left foot, took two dribbles toward the baseline and put in a right-handed layup for the first basket of the game -- a game that James and the Cavs won 96-91 for an improbable 2-1 lead in the Finals.

What happened in between James' 39-point, 50-minute effort in Game 2 and his 40-point, 46-minute performance in Game 3 is a marvel of modern sports science -- a tale of how one of the most physically imposing athletes of our time was completely depleted and then put back together.

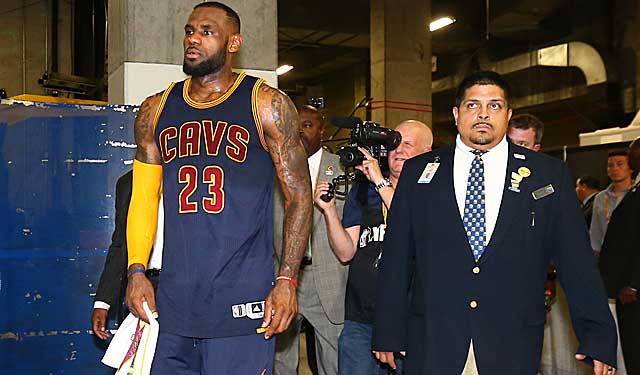

From training tools as age-old as an ice bucket to more modern accoutrements like electrical stimulation and compression sleeves, James was massaged, squeezed, flushed, frozen, heated and fueled by every trick in the sports recovery handbook. The process began immediately after he walked off the court Sunday night in Oakland and continued in every time zone until he pulled his jersey on and emerged from the home tunnel Tuesday night in Cleveland.

"I'm sure he's using everything that's out there, looking for any edge," said Tim Grover, the trainer who has famously worked with Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant and James' former teammate, Dwyane Wade.

According to a complete timeline of James' recovery protocol between Games 2 and 3 provided to CBSSports.com, it began with the simplest of training tools -- hydration and an ice bath, to replenish the critical fluids lost during Sunday night's 3-hour, 7-minute overtime game and signal to James' central nervous system it was time to switch from activity to recovery.

Imbibing a carefully prepared combination of water and carbohydrate-rich recovery fluids provided by his personal trainer, Mike Mancias, James immediately began the process of refilling his glycogen levels -- the stored form of carbohydrate found in the liver and muscle tissue. If you equate James' body to a Formula-1 racecar, refilling glycogen is as important as refueling during a pit stop.

But for James, this was no pit stop, but part of a two-day mission aimed at repairing damage from one Herculean effort in time for the next.

Next came a giant ice bucket in which James submerged himself up to his waist in the visiting locker room, even shooting a media video while inside.

The compression tights, which James wore under his sweats on his way out of the arena Sunday night, were worn to inhibit swelling during a 4 1/2-hour, red-eye flight from San Francisco to Cleveland.

"There's two things that play a part in this," said longtime Lakers strength and conditioning coach Garry Vitti, who has spent many an overnight, cross-country flight tending to Bryant during the Finals. "One is the physical exertion that they just put out for the game, and the other part is the travel because now they're changing locations."

Altitude promotes swelling and dehydration, so the fluid intake continued in-flight for James -- as did Mancias' systematic campaign against inflammation. This included a meal consisting mostly of high-quality protein and carbs and a nearly non-stop effort to flush the toxins and lactic acid from his muscles to jump-start the healing process.

James was hooked up to an electro-stimulation machine to keep his muscles contracting and enhance the flushing of toxins being pumped from his extremities by compression sleeves. The latter are Michelin-man-looking boots that fill with air with the pressure-gradient pushing blood toward James' heart.

Finally, either in a lay-back seat or on the floor, Mancias used some good old-fashioned soft-tissue massage to further squeeze out the bad stuff and make room for the nutrients James had been consuming since the game ended.

"You want to get up and move around and stretch; you don't want to get in a chair and play a video game on a four-hour flight," Vitti said.

When Jordan played, most of the work on the plane was performed manually by the Bulls' training staff, Grover said. Mancias and his colleagues around the league now have the benefit of high-tech machinery to speed the process -- not to mention power outlets and battery packs to keep it going at 30,000 feet. Still, there's no replacement for the skilled hands of a trainer on an athlete he knows well.

It sounds weird, but Mancias (who declined to be interviewed) knows James' body better than anyone except possibly his wife, Savannah. They met after Mancias was hired by the Cavs as assistant athletic trainer in 2005, James' third pro season. He got the job, in part, based on a recommendation from Grover after Mancias helped Jordan prepare for his comeback with the Wizards in 2001.

They connected when James approached him that season because he was experiencing back tightness and sore knees -- red flags, since James wasn't yet 22.

They've been together ever since -- the rest of James' first tour in Cleveland, his four Miami seasons and now back with the Cavs. Like Jordan, you can't just present a bunch of recovery protocols to James; you must be prepared to prove it to him with research, because James does his own.

"The great ones don't leave any stone unturned," Grover said. "They'll ask you questions and you've got to be ready to respond. As guys get older and get a little bit wiser, they understand how important the recovery and the nutrition part is."

The plane landed in Cleveland at about 6:30 a.m. ET, and James, 30, went home to sleep. He was back at the Cavs' training facility in suburban Independence by 1 p.m., ready for the next phase.

Light conditioning work on a stationary bike helped flush remaining lactic acid, and hot-cold contrast baths helped restart James' body and prepare it for the next bout of superhuman exertion. At this point, Game 3 was less than 30 hours away.

Sometimes, standard recovery protocol is all that's needed. Other times, there's a crisis -- like the bout of severe cramping that knocked James out of Game 1 of the 2014 Finals in San Antonio, a condition that felled unlikely Finals hero Matthew Dellavedova after Game 3 on Tuesday night. In some ways, it's easier to deal with a crisis on the road than at home.

In Game 2 of the 2000 Finals, Bryant severely sprained his ankle in a 111-104 victory at Staples Center that gave the Lakers a 2-0 lead. Vitti was facing the same kind of cross-country turnaround Mancias had with James -- an overnight flight from LA to Indianapolis and less than 48 hours between Games 2 and 3.

"The beauty of that sprain was that we were together," Vitti said. "We went from the arena to the plane from the plane to the hotel, and I changed rooms so we were side-by-side. Every few hours, I'd go in and cut the compression wrap off and treat him again."

Bryant missed Game 3, a 100-91 Pacers victory, but returned in Game 4 with 28 points in 47 minutes. The Lakers won that game in overtime, and ultimately the series -- Bryant's first of five championships.

James has no such luxury; no All-Stars or Hall of Famers on the floor with him. With Knicks castoffs Timofey Mozgov, Iman Shumpert and J.R. Smith, plus Tristan Thompson and Dellavedova, James has scored, assisted or otherwise created 200 of the Cavs' 291 points through three games.

The exertion of playing 142 of the 146 minutes in the Finals is matched only by the round-the-clock treatment and recovery program he's followed.

"That's why I've got one of the best trainers in the world in Mike Mancias who will make sure I'm ready for Game 3," James said Sunday night. "I'll be ready."

When James left the practice facility around 3 p.m. Monday, the work was far from over. Mancias showed up at James' home in suburban Bath Township, a suburb of Akron, at 6 p.m. to perform four more hours of treatment, massage and rehab.

By the time Mancias left, Game 3 was less than 24 hours away.

Tuesday was all about fine-tuning, with Mancias focusing on spots that were still stiff or sore. James' back still bothers him, and a series of hip-mobilization exercises seems to keep the pain at bay.

By about noon Tuesday, James was in the home stretch -- shooting free throws on the practice court and fulfilling his media requirements. It was T-minus nine hours to tipoff in Game 3.

"There's not much recovery time," James said. "Just getting my body as close as I can to 100 percent. I still have a lot of time right now throughout the day to stay on the treatment regimen I've been on. ... When you only have a day or 36 hours, you've got to cram everything in there. Hopefully the body reacts accordingly to it."

Nine hours from then, and 46 hours after spiking the ball and letting out that roar at Oracle, James had been restored to full capacity. Between the opening layup at 9:13 p.m. and the final horn at 11:51, James played another 46 minutes, scored another 40 points and orchestrated another improbable Finals victory.

And then, it started all over again, another round-the-clock effort to rebuild the world's best player from scratch.

"We'll be ready for Game 4," James said at the podium Tuesday night, knowing full well what that will entail.